Henry was born on January 13, 2019, at a hospital in metro Atlanta, where we lived at the time. Our little guy was five weeks early, so when labor began, we weren’t 100% certain that’s what was happening. He was our first child, and my wife is pretty tough, so I think there was a little too much “toughing it out” going on. As a matter of fact, she wanted to take a shower and do the hair-and-makeup routine before we started driving to the hospital, and I agreed and obsessively logged contractions on a contraction-timing app. When the pain knocked her to her knees in the shower, though, we knew it was time to pick up the pace. As we learned later, we almost had Henry on I-85 because my wife’s apparently ridiculous tolerance for pain didn’t create the sense of urgency we probably should have had.

Henry was born at 11:42pm on that Sunday night. Had he been born 18 minutes later, he would not have even gone to the NICU, because at birth everything seemed ok both genetically and from a health perspective. But due to being less than 35 weeks of gestation (by that 18 minutes), he spent a mandatory night in the NICU.

By that next morning, we were getting some concerning questions and observations from the medical staff. But still, there was no clarity. They wanted to run the genetic array, they said, but there was no definitive conclusion. Also, as I pulled people aside, and told them to “level with me,” veteran NICU staff were very honest in their assessments. “What do you really think?” I would say. Uncertainty—genuine uncertainty—I could see in all their faces, our OBGYN included. “That does not look like a baby with Down Syndrome to me,” he told us at the end of Henry’s first full day.

The nurse practitioner on duty in the NICU at the end of that first day was supportive as well. Or maybe we were just hearing what we wanted to hear. In any case, I remember him asking me, “Have you ever heard of Mosaicism?” “No,” I said. He explained that Mosaicism—more specifically, Mosaic Down Syndrome—was a condition where some or many of the individual’s cells carried the extra chromosome marking Down Syndrome, but not all the cells. “If anything, maybe it’s that,” he said. “But I don’t know. The test will tell us.” This man was 45 years old, and had been in NICUs for 20 years. He wasn’t giving me the run-around. He truly wasn’t sure.

Henry was born on Sunday night. We spent Monday in confusion and fear. We spent most of Tuesday praying on our knees. Then we got the test results on Wednesday afternoon, where a confirmed diagnosis of Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21) was presented.

Those were hard, dark days. Numbness. Tears. I lost 20 pounds from not eating. Even immediately afterwards, as Henry spent the next four weeks in the NICU trying to get his oxygen saturation levels up, we were pretty destroyed. We had done everything “right.” My wife was 30 years old at the time of conception, and she was in perfect health, as was I. Every OB appointment had ended with, “Everything is perfect.” I even found out weeks later, in a meeting I called with our obstetrician, that he had gone back to review the ultrasound pictures from our pregnancy, to see if he had missed physical signs or markers of Down Syndrome that are typically noticeable in the ultrasound images. No, he said. They just weren’t there.

That first year was hard. Pediatrician appointments. Speech therapy for potential aspiration. County Department of Health appointments in dark, depressing buildings with seemingly uncaring staff. Cardiology appointments. Open-heart surgery at six months old. It was just…a lot.

My wife and I had each other, though, and we also knew that our little boy was tough. We knew that there was never a better time to be born with Down Syndrome. Early intervention opportunities—which we believe are an absolute critical component to early and prolonged success for our child and others with his condition—are prevalent. Social inclusion is improving all the time, and is profoundly better than it was when we were children. College programs now exist with proven track records for helping children like our son live a fulfilled and contributory adult life.

Beyond all that, we believe that our son is, in fact, our son. Therefore, he has no choice but to be tough, resilient, smart, hard-working, athletic and handsome. Sure, there will be some differences in developmental pace that we will need to be patient with, but our expectations are literally no different for our little boy than they would have been with a perfectly healthy delivery.

We do owe a debt of gratitude to the Meyer Center for Special Children here in Greenville, as they took Henry in at nine months old—the youngest student they have ever taken—and he has thrived. The developmental structure that they provide, along with the genuine love that is apparent from their staff, has been life changing. No minute goes unplanned. No day goes without stimulation, from social interaction to physical therapy to music therapy. It is an amazing place.

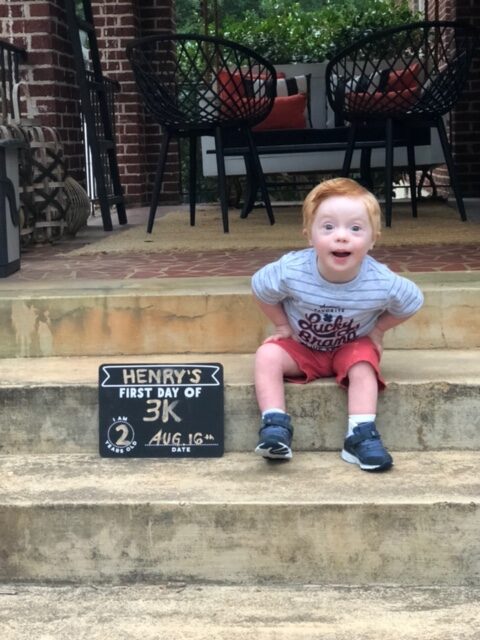

And as Henry Hope Holmes approaches his third birthday, his life and our life are pretty great. He’s an extremely smart young man who likes to organize things, clean up, and boss around his 11-month-old sister. He’s funny, he’s helpful, and loves the camera. From his third day, when we decided to make his middle name “Hope,” we have tried to focus on upsides and on possibilities. We have hope for him, just like we would for any child, and we will do everything in our power to open doors for him, just like our parents did for us.

Recent Comments